The Persian Tobacco Protest

The Persian Tobacco Protest, was a Shi’a revolt in Iran against an 1890 tobacco concession granted by Naser al-Din Shah Qajar of Persia to Great Britain, granting British control over growth, sale and export of tobacco. The protest was held by Tehran merchants in solidarity with the clerics.

On 20 March 1890, Naser al-Din Shah granted a concession to Major G. F. Talbot for a full monopoly over the production, sale, and export of tobacco for fifty years. In exchange, Talbot paid the shah an annual sum of £15,000 (present-day £1.845 million; $2.35 million) in addition to a quarter of the yearly profits after the payment of all expenses and a dividend of 5 percent on the capital. By the fall of 1890 the concession had been sold to the Imperial Tobacco Corporation of Persia, a company that some have speculated was essentially Talbot himself as he heavily promoted shares in the corporation. At the time of the concession, the tobacco crop was valuable not only because of the domestic market but because Iranians cultivated a variety of tobacco “much prized in foreign markets” that was not grown elsewhere. A Tobacco Régie (monopoly) was subsequently established and all the producers and owners of tobacco in Persia were forced to sell their goods to agents of the Régie, who would then resell the purchased tobacco at a price that was mutually agreed upon by the company and the sellers with disputes settled by compulsory arbitration.

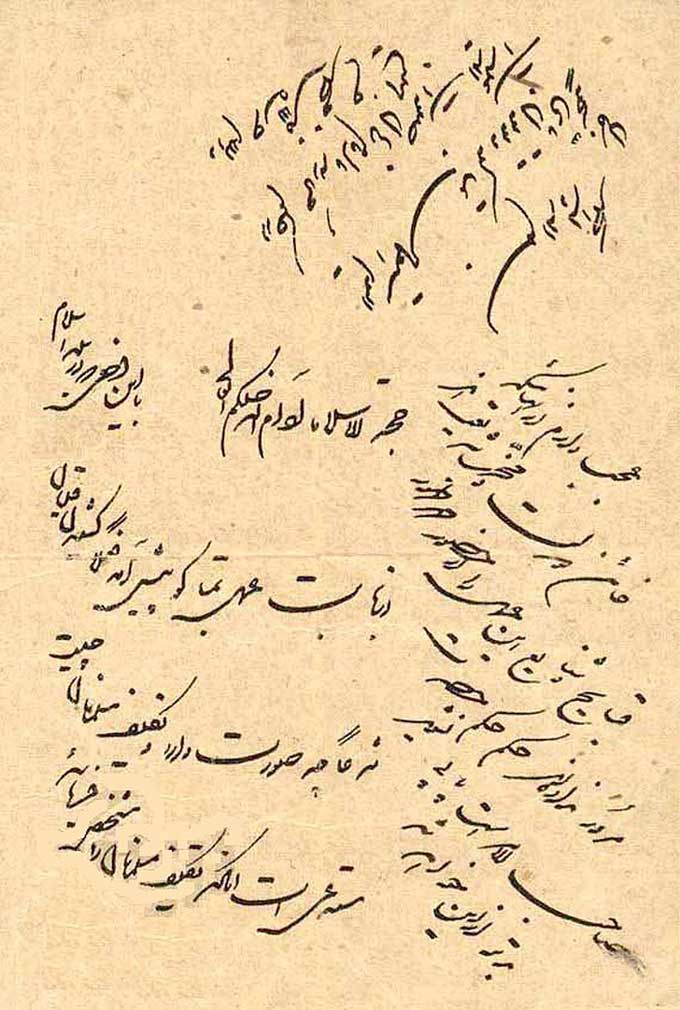

In December 1891 a fatwa was issued by the most important religious authority in Iran, Grand Ayatollah Mirza Hassan Shirazi, declaring the use of tobacco to be tantamount to war against the Hidden Imam, Muhammad al-Mahdi. The reference to the Hidden Imam, meant that Shirazi was using the strongest possible language to oppose the Régie. Initially there was skepticism over the legitimacy of the fatwa; however, Shirazi would later confirm the declaration.

Iranians in the capital city of Tehran refused to smoke tobacco and this collective response spread to neighboring provinces. In a show of solidarity, Iranian merchants responded by shutting down the main bazaars throughout the country. As the tobacco boycott grew larger, Naser al-Din Shah and Prime Minister Amin al-Sultan found themselves powerless to stop the popular movement fearing Russian intervention in case a civil war materialized.

Prior to the fatwa, tobacco consumption had been so prevalent in Iran that it was smoked everywhere, including inside mosques. European observers noted that “most Iranians would rather forego bread than tobacco, and the first thing they would do at the breaking of the fast during the month of Ramadan was to light their pipes.” Despite the popularity of tobacco, the religious ban was so successful that it was said that women in the shah’s harem quit smoking and his servants refused to prepare his water pipe.

By January 1892, when the shah saw that the British government “was waffling in its support for the Imperial Tobacco Company,” he canceled the concession. The fatwa has been called a “stunning” demonstration of the power of the marja’-i taqlid, and the protest itself has been cited as one of the issues that led to the Constitutional Revolution a few years later.

For more information, visit https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tobacco_Protest.